On the occasion of the 76th anniversary of the liberation of the Flossenbürg concentration camp, we are telling the stories of eight survivors after their liberation in the form of short film clips. Affected by their imprisonment and persecution, they tried to find their way back into life. The new beginning is associated with different challenges and feelings. All survivors, however, share the question: „Where do I go from here?“

On the occasion of the 76th anniversary of the liberation we were looking forward to getting together with survivors, their families, politicians, representatives of victims’ associations and of public figures. Sadly, we have to forego the personal meetings and exchange again. To allow a dignified remembrance of the 76th anniversary of the liberation, we want to shed light on life after imprisonment in a concentration camp with the help of eight biographies.

The short films give insights in the survivors’ efforts to build a new life, the adversities they were confronted with, and their struggle for recognition. They are stories of trauma and feelings of guilt, of loss and recommencement, pain and healing, as well as witnessing and silence. For none of the survivors the beginning of the new life was easy.

Flossenbürg Memorial commemorates the fate of the around 100,000 prisoners of the Flossenbürg camp system. At least 30,000 of them died in Flossenbürg or in one of its around 80 subcamps.

On the site itself two permanent exhibitions inform about the history of the concentration camp and its aftermath up to the present day.

Supported by

KZ Gedenkstätte Flossenbürg

Gedächtnisallee 5

D-92696 Flossenbürg

+49 9603-90390-0

information@gedenkstaette-flossenbuerg.de

www.gedenkstaette-flossenbuerg.de

ImprintImage Credits

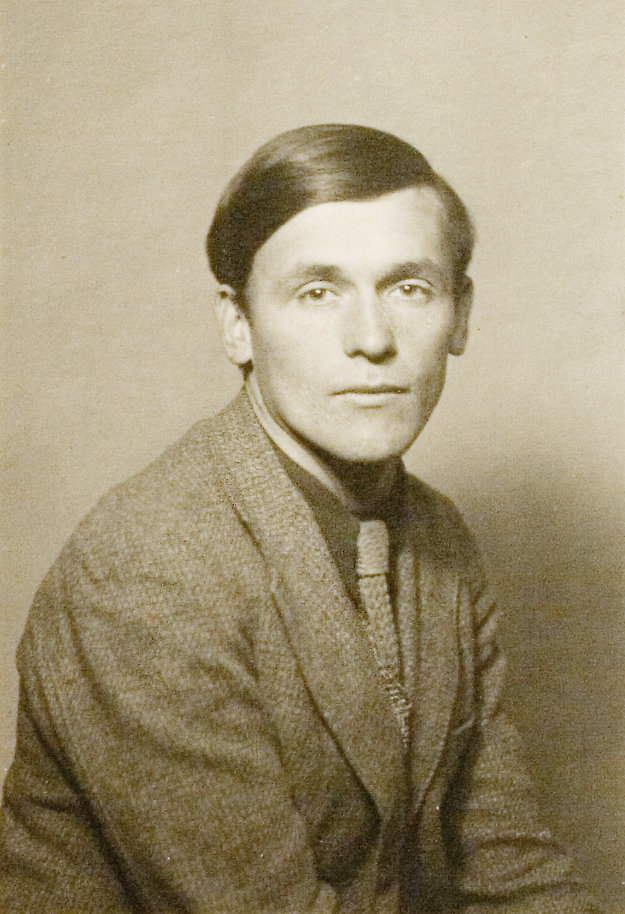

Richard Grune (August 2, 1903 – November 26, 1984)

Richard Grune grew up with seven siblings in a family of social democrats. At an early age, he began to draw. With the support of his parents, he started training as a commercial artist at the Tradesman and Applied Arts School in Kiel at the age of 16. In 1922 he took two preliminary courses at the Bauhaus in Weimar with Johannes Itten but was rejected when he applied as a student. Despite the rejection, Itten’s work continued to shape Grune’s own work even decades later. Grune held his first exhibition in Kiel in 1926, for which he received widespread public recognition.

In February 1933, Grune moved to Berlin. Against the backdrop of waves of raids on homosexuals, the Gestapo arrested him in autumn 1934. He was imprisoned in Neumünster prison and several concentration camps for offenses against Paragraph 175 until the end of the war. At the beginning of April 1940, the SS transferred Richard Grune from the Sachsenhausen concentration camp to the Flossenbürg concentration camp. On assignment by the SS, the artist had to work in the “Künstlerkommando” (the “Artists’ Commando”). Together with friends like Albert Christel, he secretly made poems and drawings in which he recorded the experiences of his imprisonment in the concentration camp. Yet, it wasn’t just drawing that saved Grune’s life. Unlike most homosexual prisoners, who were often left to fend for themselves, Grune relied on the help of other imprisoned social democrats because of his social democratic past. This also helped him after the war.

After the liberation, Grune returned to Kiel. His strong inner need to educate people about the terror and horrors in the concentration camp was given artistic expression. Within a few weeks, Richard Grune created more than 40 drawings with scenes from the camps. Beginning in autumn 1945, he exhibited his drawings in several German cities in the British and American occupation zones. The traveling exhibition “Die Ausgestoßene” (“The Pariahs”), however, aroused little interest among the general population. Grune was once again convicted in 1948 for homosexual acts. The refusal to recognize him as a victim of National Socialist violent crimes and the renewed persecution had a profound effect on him. With his emigration to Spain in the mid-1950’s, he hoped to escape the tight moral corset of the Federal Republic. However, financial difficulties forced him to return to Northern Germany in 1962. He passed away on November 26, 1984 in a nursing home in Kiel.

“After I was liberated in 1945, I saw it as my duty to educate people about the concentration camps and the terror of the Third Reich.” [Must be spoken by another narrator].

When the artist Richard Grune returned home in the summer of 1945, he immediately began to process the experiences of his eight-year imprisonment through art. With an intense inward drive, he painted uninterrupted. Within a few weeks, he created more than 40 drawings with scenes depicting imprisonment in the camps.

In September 1945, with the help of his sister, Grune began showing his paintings as a traveling exhibition in several German cities, under the title “Die Ausgestoßenen” {“The Pariahs”}. At the time it opened in the heavily damaged “Fränkische Galerie” in Nuremberg at the beginning of 1946, the crimes of the National Socialists were being tried before the International Military Tribunal. Grune had hoped, in the former city of the Nazi party rallies, to demonstrate the horrors of the camps to a large domestic and international public.

At the opening of the exhibition a few months later in the Erlangen Orangery, the mayor paid tribute to Grune as a “witness against the rule of violence […] for peace and […] a new democratic order.” However, Grune’s exhibitions were less popular with the public. The exhibition in Kiel was vandalized by unknown assailants. Two portfolios of his works were a financial failure. The majority of Germans were not interested in the fate of those who were once imprisoned.

Grune, who was persecuted by the National Socialists for his homosexuality, was also denied social recognition as a victim. Male homosexuality after the war was, after all, still a criminal offense. In 1948, Grune was sentenced again to eight months in prison for homosexual acts.

In a letter he wrote while in custody, he lamented, “That is too harsh a punishment for such a case and it comes closer to the penalties of the Third Reich than those before 1933.”

Grune, who increasingly felt like an outsider, hoped for a new life in Spain. After he had moved to Barcelona in the mid-1950s, his drawing style also changed. Instead of detailed depictions, Grune now used simple, clear lines. His preferred subject became everyday scenes from life in the Catalan capital. However, financial difficulties forced him to return to Germany in 1962. A new beginning as an artist in his old home became something he no longer ventured to do. Richard Grune died in a nursing home in Kiel in 1984. It was not until years later that his works on the concentration camps were rediscovered and recognized internationally as early evidence of the cruelty and terror in the camps.

Tabs

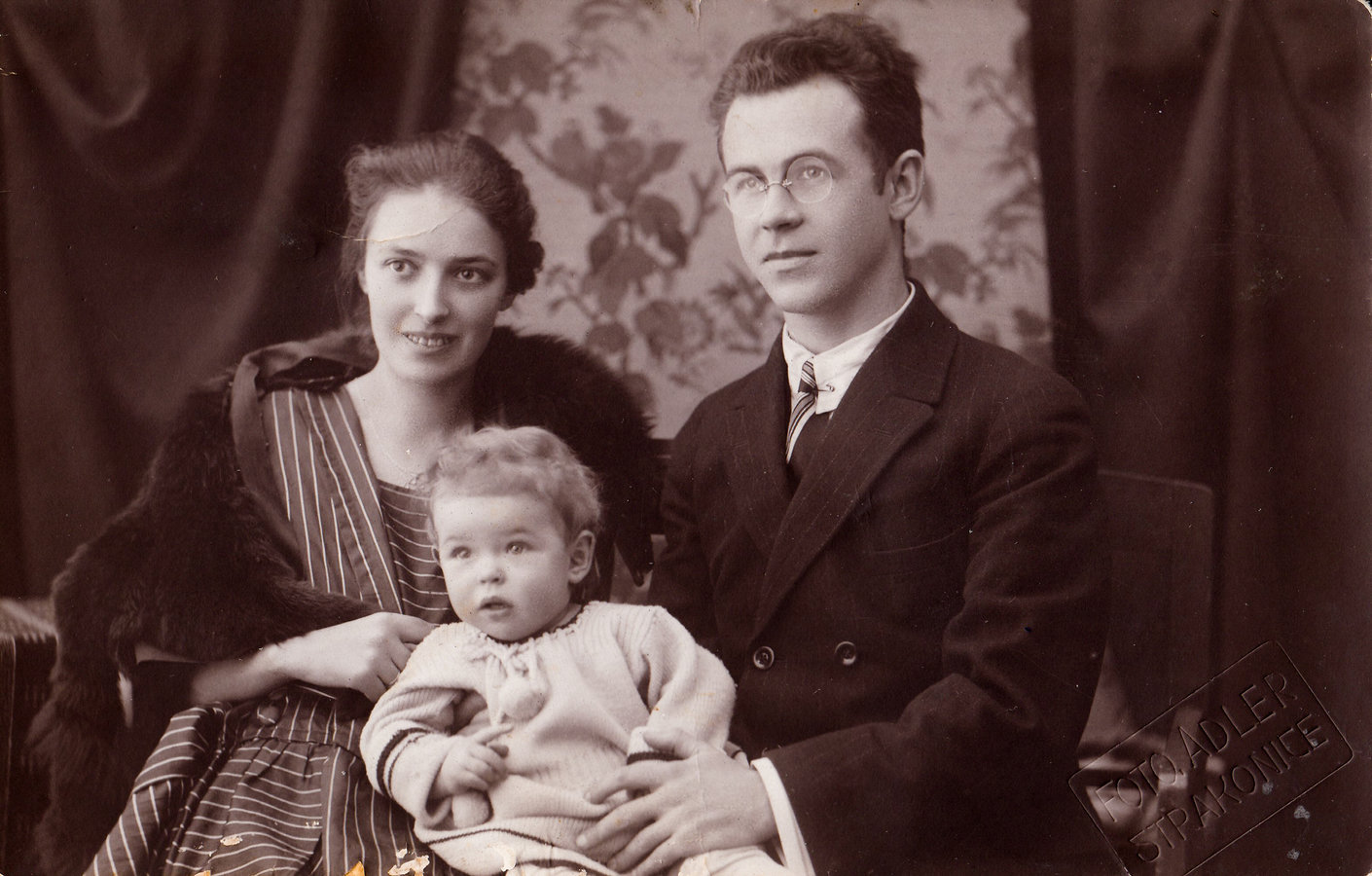

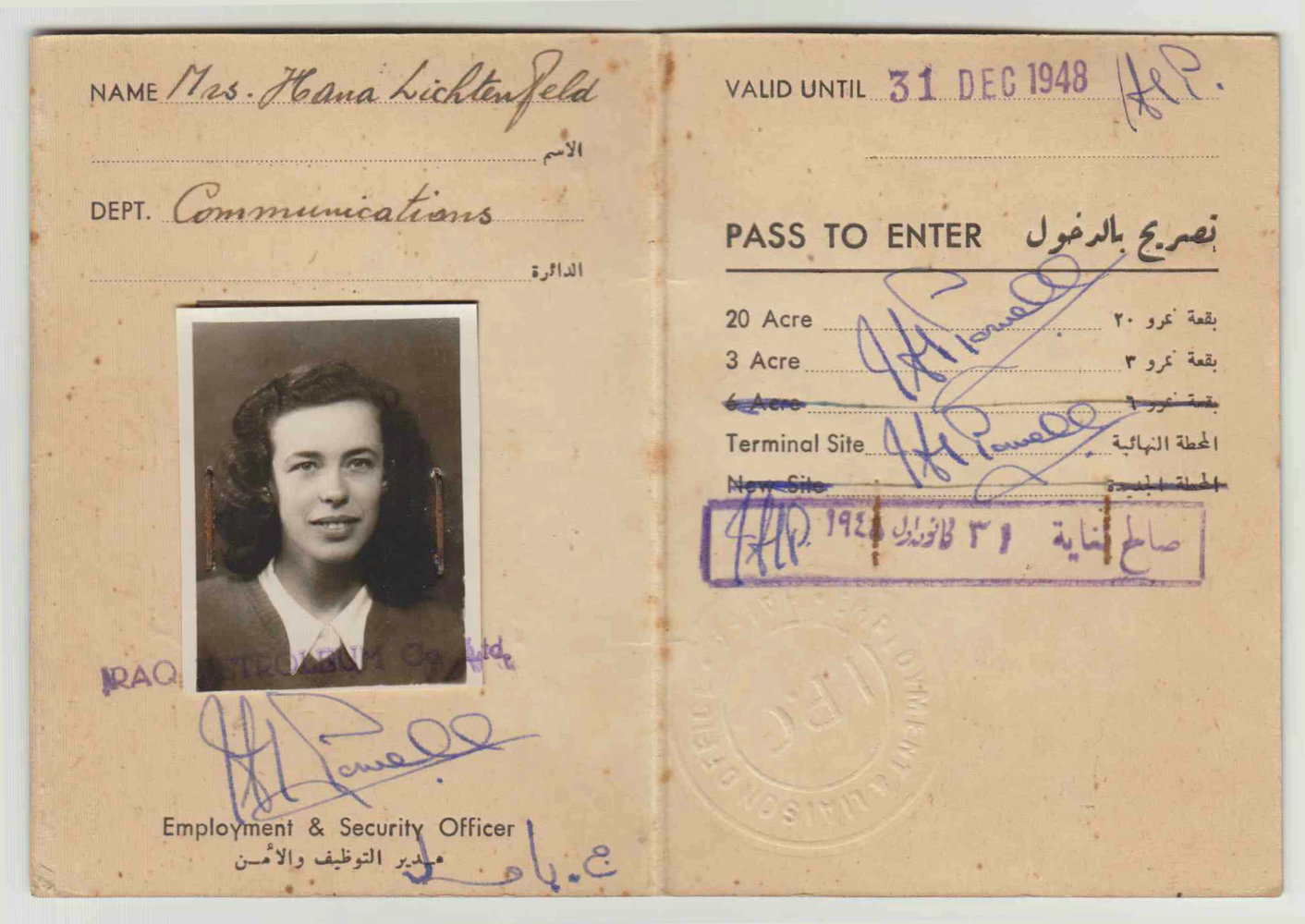

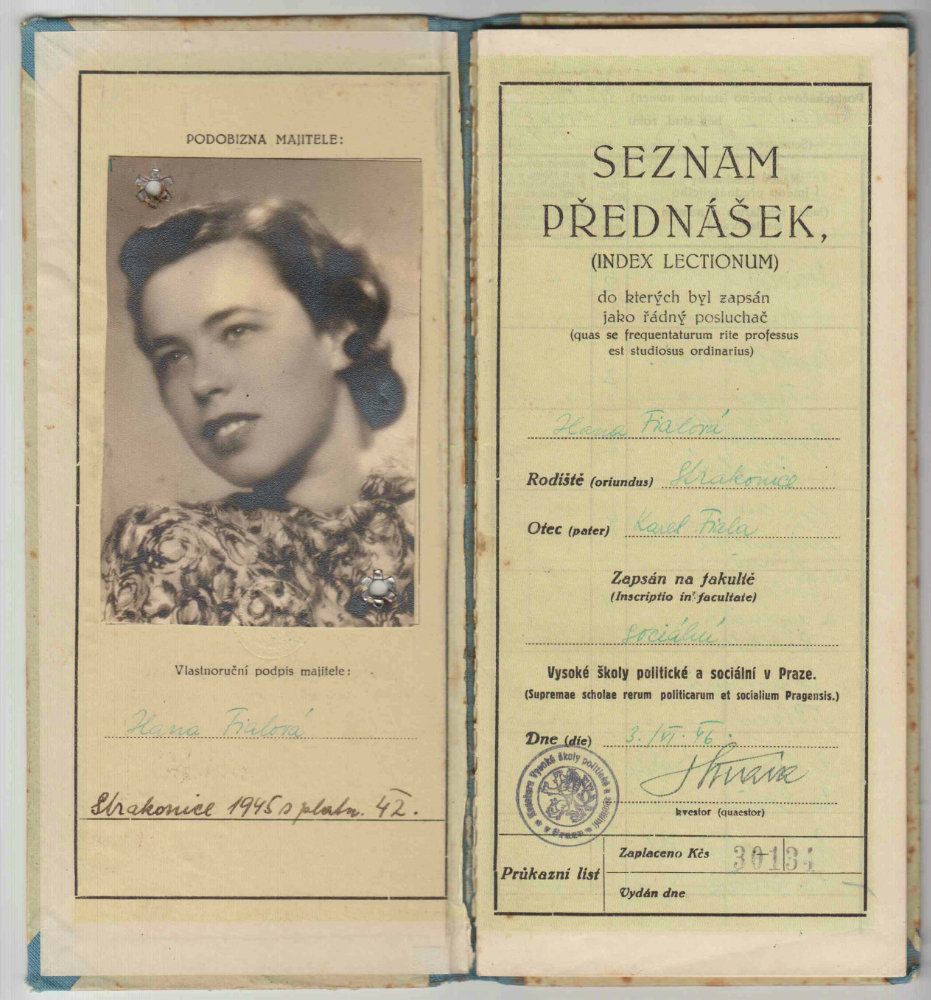

Hana Malka (b. February 21, 1923)

Hana Fialová grew up in Strakonice, Bohemia (present day Czech Republic). As a Jewish girl, Hana had a sheltered and lovely childhood. When the German Wehrmacht invaded Czechoslovakia in the spring of 1939, life changed for the Jewish population. Hana had to drop out of school and her family was dispossessed. In November 1942, the young woman, her mother, and her grandfather were forced to move to the Theresienstadt ghetto. After two years in the ghetto, she was transported to Auschwitz. The SS classified her as “fit for work” and transferred her to the Oederan subcamp of Flossenbürg near Chemnitz.

At first, Hana Fialová cleaned and darned stockings for the guards. However, when the supervisor thought that Hana was becoming complacent with these duties, she was forced to work for the Deutsche Kühl- und Kraftmaschinen GmbH, manufacturing bullet casings. This work was especially dangerous during the night shift, because women were easily injured due to exhaustion. At the end of April 1945, the SS transported the prisoners in cattle cars towards Bohemia. In order to be able to flee from the Allies in time, the guards sent the female prisoners the last stretch towards Theresienstadt without being guarded. On May 8, 1945, the Red Army liberated Theresienstadt. Soviet soldiers took Hana Fialová with them on a tank and drove in the direction of Prague.

Only a handful of Hana’s distant relatives survived the war; nothing was keeping Hana in Europe. She decided she wanted to emigrate to Palestine, which she was able to do legally, thanks to a sham marriage. She later met Meir Malka, eventually marrying him and starting a family with him. Together they have two children and five grandchildren.

Hana Malka travels frequently, is involved with her community, and works as a Feldenkrais teacher into old age. She also regularly visits the Flossenbürg Concentration Camp Memorial and speaks with young people about her experiences, engaging them in a dialogue about the past and present.

“How do I get to Palestine?” 23-year-old Hana Fialová asked herself in 1946. Being a Czech Jew, she had survived the Holocaust. After the liberation, Hana began studying sociology in Prague, but she really wanted to go to Palestine.

After the war, it was most notably Jewish survivors who were confronted with the fact that they were the only surviving members of their families and that they had lost their homes. Many of them therefore dreamt of a Jewish state in Palestine, with the desire to leave Europe behind. They hoped that a state of their own would give them security. But entry into Palestine was difficult. The British, who administered the area, allowed few people to immigrate. Many survivors therefore attempted to illegally enter the country. When discovered, they faced internment in a camp and the forced return back to Europe.

Hana Fialová thus sought another way to emigrate to Palestine. “I wanted to go to Palestine. And then they made it possible for me to go to Palestine. I entered into a fake marriage. Because people who were in the British Army and had been in Palestine before were able to return with their families. And if a boy didn’t have any family, they gave him a wife in a fake marriage, so that he could bring her to Palestine legally. So arrangements were made for me, a fake marriage. And I was able to go to Palestine legally.”

Jewish organizations facilitated numerous fake marriages with British soldiers stationed in Palestine. Since they were allowed to take their wives with them to Palestine, arranged marriages were one of the few opportunities for Jewish women to immigrate legally. On July 15, 1946, in Prague, Hana married Imrich Lichtenfeld, 13 years her senior. Like a majority of these marriages, Imrich and Hana divorced shortly thereafter.

Yet, for the young woman, the marriage certificate was most importantly the ticket to a new life. In the summer of 1946, she arrived, without Imrich Lichtenfeld, in her new home. As for most emigrants, the new beginning was more difficult for Hana than she had imagined. She lived at first with her uncle. Since she did not have the money to resume her studies, she worked as a cleaning lady and later a telephone operator.

Hana met Meir Malka at the end of the 1940’s. The two fell in love, got married, and started a family.

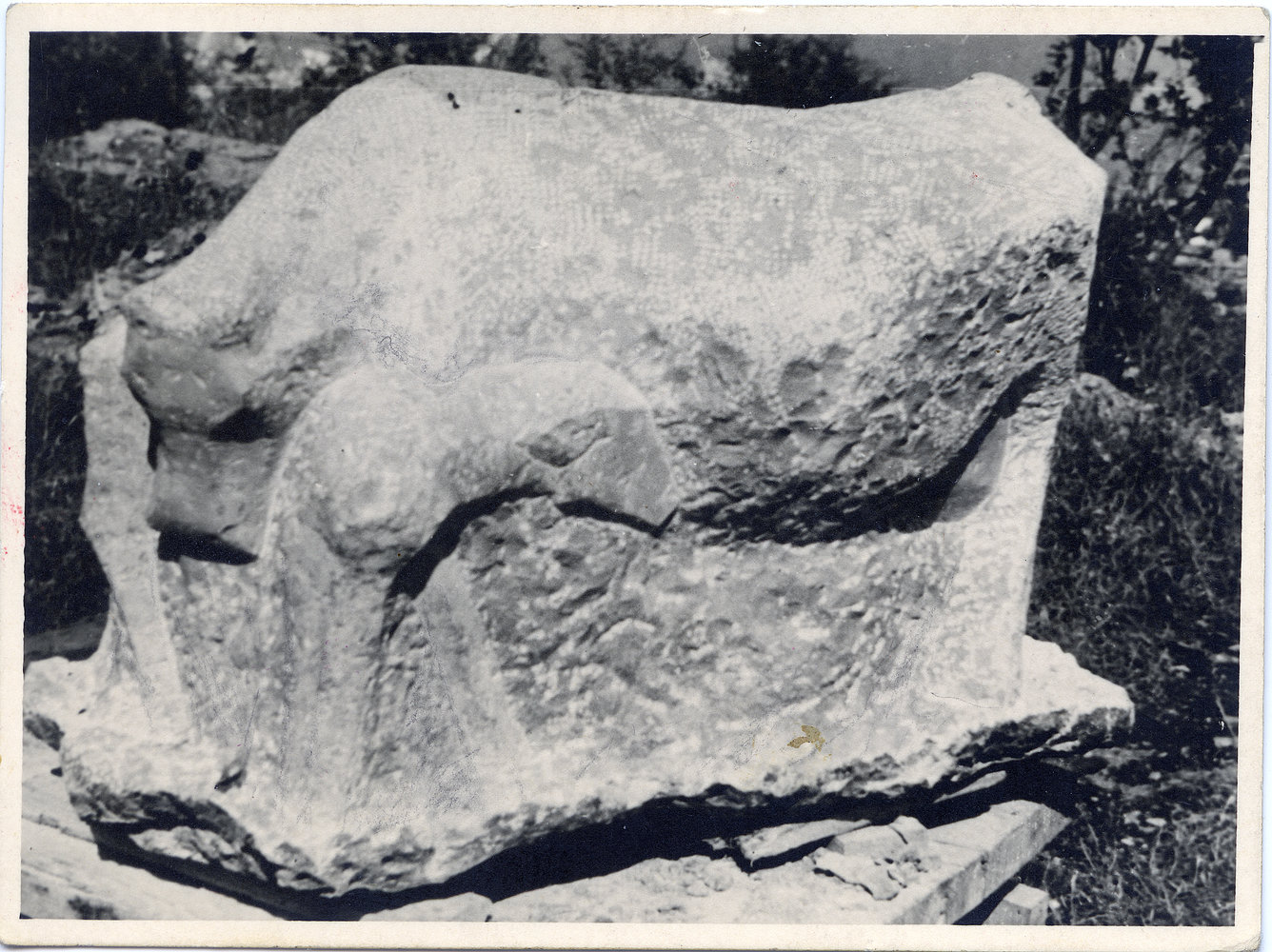

Shelomo Selinger (b. May 31, 1928)

Shelomo Selinger grew up in Szczakowa, Poland. His family maintained Jewish cultural values but was not strictly religious. After the Wehrmacht invaded Poland in 1939, the eldest sister Sara was deported to a labor camp, while the rest of the family was forced to move to the Krenau Ghetto (Polish: Chrzanów), where they made clothes for the German army. In 1942, Shelomo and his father were separated from the rest of the family. While the mother Helena and younger sister Ruiji were being murdered in a death camp, the SS deported Shelomo and Abraham to Faulbrück, a subcamp of the Groß-Rosen concentration camp. Three months later, the SS murdered the physically weakened Abraham Selinger. Following the liquidation of the Groß-Rosen camp complex, Shelomo Selinger and 2,000 other prisoners were transferred to the Flossenbürg concentration camp, arriving on February 13, 1945.

Selinger found the beauty of the landscape of Flossenbürg contrasted with the cruelty and privation of the camp particularly demoralizing. At the end of March 1945, the SS transferred him to the Dresden Reichsbahn subcamp. There he repaired destroyed railway tracks. When this camp was also liquidated, the prisoners were forced on a grueling march to the Theresienstadt Ghetto. At the liberation by the Red Army, Selinger was so weak that he was presumed dead and was laid with the corpses. A military physician discovered him and took care of the young boy until he regained his strength. Deeply traumatized from his imprisonment in the camps, he suffered from amnesia, which lasted for over seven years.

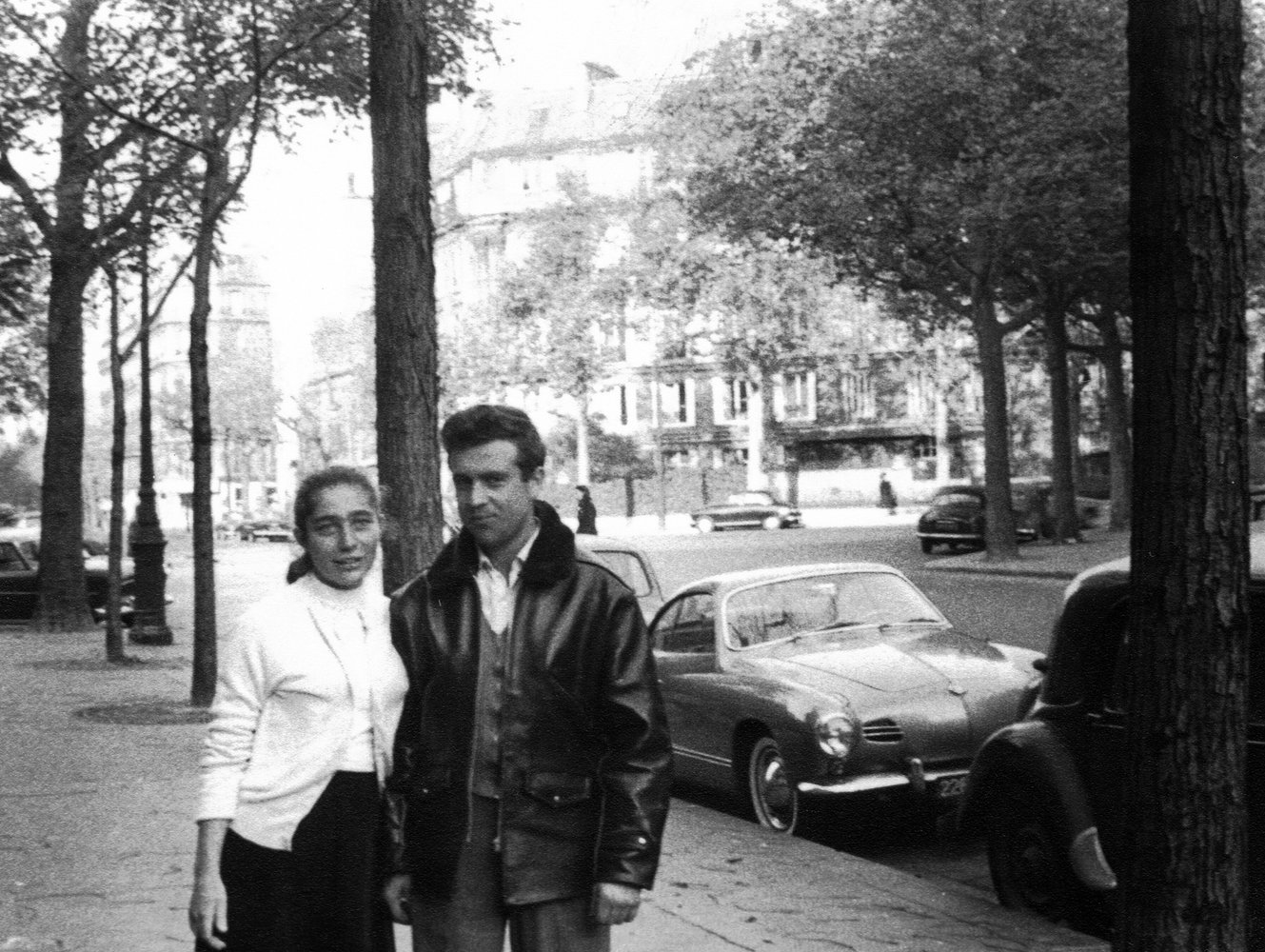

In 1946 Selinger emigrated to Palestine with other survivors. He settled in a kibbutz on the Dead Sea and fought in the Israeli War of Independence in 1948. Meeting his future wife Ruth Shapirovsky in 1945 led him to sculpture. She helped Selinger, whose memories at the time were slowly returning, to process his experiences of persecution.

In 1955 the couple moved to Paris. Selinger started studying at the École des Beaux Arts. His encounters with Hans Arp and Constantin Brâncuși, who were among the most influential artists of time, had an effect on him. This was the beginning of his life as an artist, which spanned more than six decades. His prize-winning work has been exhibited worldwide. To this day, Shelomo Selinger works in his studio every day.

After several grueling death marches, Shelomo Selinger experienced the end of the war in the Theresienstadt Ghetto. He was so weak that he was presumed dead. “A Soviet officer came closer. He saw that I was not really dead, took me out of there, and brought me to the military hospital. And the director of the hospital personally came by at particular intervals and gave me two or three spoonfuls of soup. Slowly, he gave me back my life. He did not want me to die. I regained my strength little by little.” Only through the help of a Jewish military physician from the red army, the 15-year-old was able to survive.

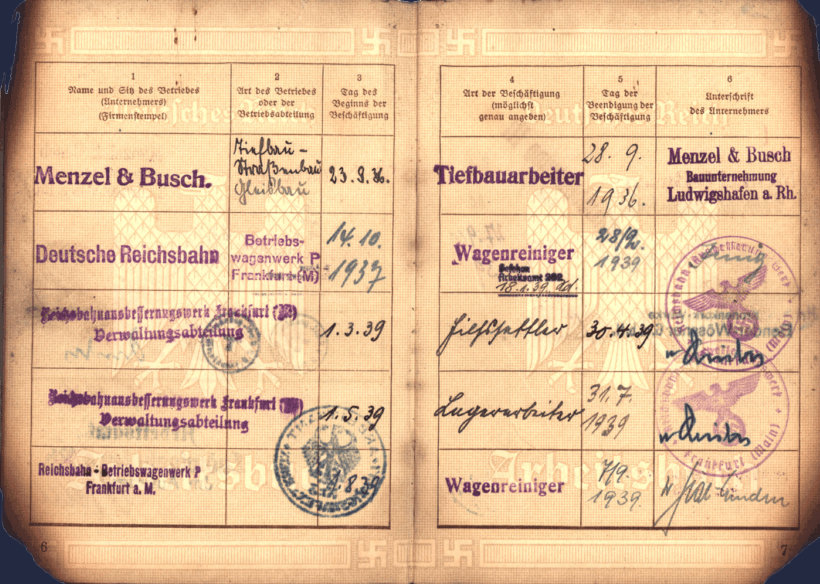

Years of persecution and imprisonment, as well as the inhumane conditions in the camps, left the survivors physically emaciated. At the time of liberation, many of them were more dead than alive. Therefore, the medical care of the seriously ill became one of the most urgent tasks of the Allied military units. For many, however, this help came too late. The physical and mental wounds suffered during their imprisonment in the camps accompanied the survivors throughout their entire lives.

So too was Shelomo Selinger severely traumatized. He suffered from amnesia, barely recalling his family or his time in the camps.

In 1946, Selinger emigrated to Palestine and settled in a kibbutz on the Dead Sea. Life was difficult, but Selinger relished the newly acquired freedom. He speaks of being “born again” there in the light of the desert.

Meeting his future wife Ruth in the early 1950s introduced Selinger to sculpture. His memories also slowly returned. Nighttime was when he was especially haunted by the shadows of the past. The creative work helped him to cope with what he experienced. However, the memory of it will never leave him again.

In the course of his life, the worldwide-renowned artist created more than 800 sculptures from different materials.

The themes are often family, the joy of life, or survival.

At first glance, very few of his artworks have any visible reference to the Holocaust.

Oscar Albert (August 30, 1926 – January 10, 2012)

Avaram Yoshua ben Mordeschai Schlomo Albert, nicknamed Shia, grew up in Rzeszów, Poland. Two days after his 15th birthday, the Wehrmacht invaded Poland; two weeks later, the Red Army seized the east of the country. Shia’s father, who fought as a soldier in the Polish army, was taken prisoner by the Soviets. Like all other Jewish men between the ages of 14 and 60, Shia was required to do forced labor for the German occupiers. He was interned in various forced labor camps on Polish soil until 1944. In Rzeszów, Mielec, Budzyń, and Wieliczka he had to work in aircraft production for the companies Daimler-Benz, Heinkel, and Henschel. In Mielec a guard knocked out almost all of his teeth with the butt of a rifle. He was deported from Wieliczka, a satellite camp of the Plaszow concentration camp, to the Flossenbürg concentration camp at the beginning of August 1944. His mother was murdered two years earlier at the Belzec death camp. The fate of his two sisters remains unclear to this day.

In Flossenbürg Shia again assembled aircraft, this time for Messerschmitt. When he fell ill with typhus, a German foreman hid Shia in an aircraft fuselage, the main body section of an aircraft, so he could recuperate, secretly bringing him food. When the SS dissolved the camp in mid-April 1945, Shia Albert was forced on a death march in the direction of Dachau. Along the way exhausted prisoners were repeatedly shot and killed. Right before Shia Albert was about to lose strength, the SS men deserted the inmates, fleeing from the approaching American units.

After the war, before he emigrated to the USA in 1949, the young man lived in a DP camp in Schwandorf, in the Upper Palatinate. He changed his name to Oscar. When he learned that the German foreman who helped him in Flossenbürg was classified as an accomplice to Nazi crimes, therefore not receiving ration cards, Oscar advocated for him at the US military administration. After emigrating to the USA, he never set foot on European soil again; although, as a manager of a US toy manufacturer, he traveled all over the world on business. In 1954 Oscar Albert married Diana, a survivor of the Warsaw ghetto, in New York. With his impressive singing voice, he was a valued member of the New York Jewish community as a cantor. Oscar Albert spoke little about his experiences during the war with his family. He always covered the tattoo on his right forearm, given to him at the Mielec camp to identify him as a prisoner, with a large watch. Oscar Albert passed away in 2012.

In 1994, when Oscar Albert visited the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington D.C. with his daughter Helen, he paused for a longer moment in front of a photo from the Flossenbürg concentration camp. It showed prisoners at work in the quarry. This was the first and only time he talked with his daughter about being in the camp. After the death of her father in 2012, Helen found a box with numerous documents and photos in his closet. It took more than two years for Helen Albert to try and reconstruct the past of her father. The individual pieces of the puzzle only gradually came together for her.

For the first four years after the end of the war, Oscar Albert lived in a camp for Displaced Persons in Schwandorf, Upper Palatinate. During the six-week stay in the Schwandorf hospital, he slowly recovered. As a symbol of survival, he let his hair grow out long. Despite his traumatic experiences and the uncertainty about his future, Oscar Albert tried to lead a normal life. He spent time with friends, played soccer, and traveled. His German shepherd Benito is named after the Italian dictator. After two years, the young man was reunited with his father. With the support of relatives, they emigrated together to the USA in 1949.

Oscar Albert began a new life: he became a successful businessman, married and started a family. Those who knew him described him as friendly, warm-hearted, and humorous. It was apparent to those around him that he chose to look forward rather than back. Oscar Albert preferred to give his painful memories as little space as possible in his life. Like many other survivors, he remained silent about his experiences in the camps throughout his life.

“I think that part of the reason he didn’t talk about it was I just think he didn’t want it to define him. Even to his family. Why would we look at him that way? Did I ask him? No. I think I knew subconsciously that he didn’t want to go there. And you know what? I didn’t want to go there either. But because my profession – I am a investigator – after he died I felt somewhat liberated to try to find out. I didn’t need to upset him. You know whatever. Though I became almost passionate about finding out. But I was 50 when that happened.”

Jekaterina Filippowna Dawidenkowa (b. March 14, 1926)

Jekaterina Filippowna Dawidenkowa grew up with four sisters in the city of Jarzewo near Smolensk. When the war began, she was still a student in school. The first months of the war were characterized by bombings and fights between the Soviet and German armies. Her father was the commander of a partisan group that Jekaterina Dawidenkowa also eventually joined. She performed small tasks, such as monitoring and reporting on rail traffic. However, one night in December 1943, Jekaterina Dawidenkowa was arrested by the Germans.

She spent several months in prison, enduring repeated violence and solitary confinement. In April 1944 Jekaterina Dawidenkowa was taken to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. The number 79663 was tattooed on her forearm. Every day, she and other inmates performed forced labor. Six months later, in October 1944, the SS transported her to Mittweida/Saxony, a subcamp of the Flossenbürg concentration camp. Around 500 women were quartered there in a factory building, producing iron and artificial resin parts for electrical devices.

In mid-April 1945 the camp was liquidated. Jekaterina Dawidenkowa and the other women were transported across the Czech border in open train cars. On April 27, 1945, the train stopped at the Prague-Bubny station. There, with the help of Czech civilians, Dawidenkowa and four other prisoners managed to escape. Dawidenkowa experienced the end of the war in Prague.

Like many others, Jekaterina Dawidenkowa wanted to return to her home country. However, the Soviet government suspected former prisoners of war, forced laborers, and concentration camp inmates of collaborating with the National Socialist regime. When returning to the Soviet Union, they were therefore required to go through so-called “screening and filtration camps.” There Jekaterina Dawidenkowa was interrogated about the circumstances of her detention and given a medical examination. Even years later she still spoke of this procedure as being humiliating. Lifelong she dealt with the distrust of the Soviet state that was cultivated on her return home.

After the investigation at the filtration camp, Dawidenkowa first returned to the destroyed Smolensk, then later to her hometown of Jarzewo. There she learned that her parents did not survive the war. Jekaterina Dawidenkowa married and worked as a civil engineer, first in Leningrad, then later Moscow. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, she visited the Flossenbürg Concentration Camp Memorial for the first time in the mid-1990s.

Shortly before the end of the war, Jekaterina Filippowna Dawidenkowa managed to escape from a prisoner transport. She experienced the end of the war in Prague. Like many others, she wanted to return to her home country.

But the Soviet government suspected the former concentration camp prisoners of collaborating with the National Socialist regime. Therefore, on their return to the Soviet Union, almost all of the Soviet survivors were required to go through the so-called “testing and filtration camps.” At one of these camps Jekaterina Dawidenkowa was interrogated about her imprisonment. Even decades later, the former prisoners speak about how they felt these often-intimate questions and the treatment by the Soviet authorities were meant to be deliberately humiliating.

However, she was cleared by the investigation and was allowed to return to her home country. What remained was a lifelong distrust. After completing her training at the University of Applied Sciences for Civil Engineering in Moscow, Jekaterina Dawidenkowa married her longtime fiancé. He was an officer in the Soviet Army. When her husband was supposed to be relocated, his private life was scrutinized. “And when they found out that I was in captivity in Germany, I was pretty much considered a traitor to the people. […] He was given a choice: he had to either give up his epaulettes or leave me. Either his service or me. Well – he left; he didn’t even say goodbye to me.”

Dawidenkowa raised their son alone. She found a job as a civil engineer and was promoted to the head of the department. But the distrust of the Soviet state remained and permeated almost all areas of her life.

Her experiences in the concentration camps were also often present in her life. When she heard the German language once again years later, the memories overcame her. “Of course this past haunts me all the time. This war. Sometimes it is dogs. Other times someone would be told, “You are not allowed to work there; you are not allowed to drive there; you are not allowed to do this or that” — it’s incomprehensible.”

With Stalin’s death in 1953, the political and social situation changed. Starting at the end of the 1950s, the survivors were able to organize and network for the first time. Even if the suffering of the former concentration camp prisoners did not play a role in the Soviet commemoration of World War II, the exchange with other survivors helped Dawidenkowa to cope with her past.

- Bayerischer Architekten- und Ingenieur-Verband

- Deutsche Fotothek, Roger Rössing

- Kreisarchiv Mělník

- KZ-Gedenkstätte Flossenbürg

- Militärhistorisches Archiv, Prag

- Mittelböhmisches Museum, Roztoky

- Národni archiv, Prag

- Privatbesitz

- Romanov Empire, Historical Society

- Staatsarchiv der Russischen Föderation, Moskau

- Vojenský historický archiv VÚA

- Wikipedia

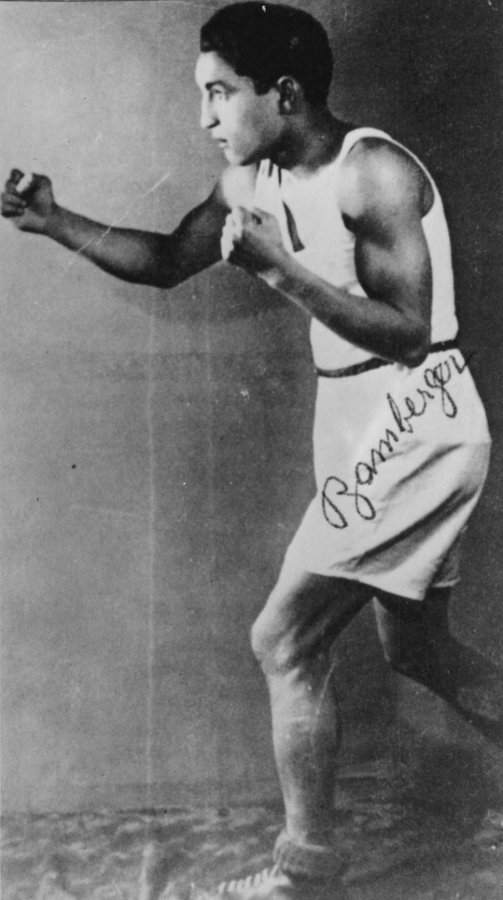

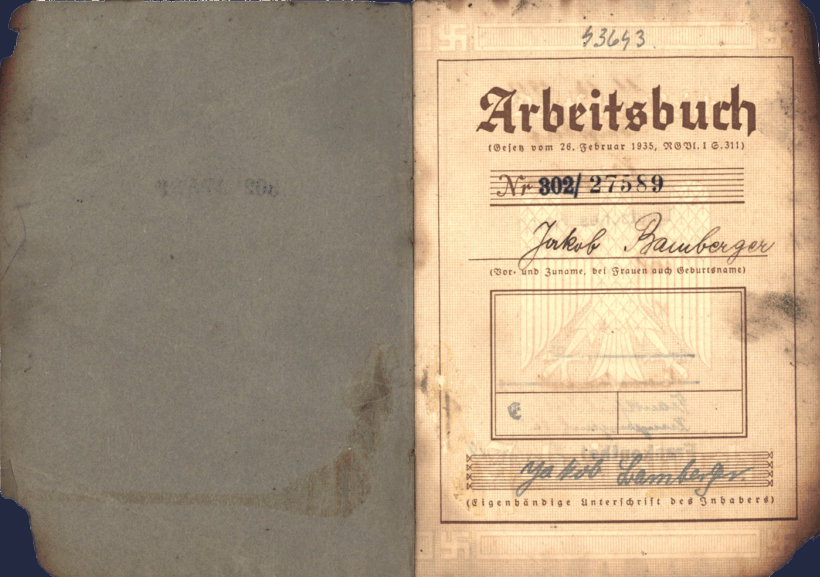

Jakob “Jonny” Bamberger (December 11, 1913 – 1989)

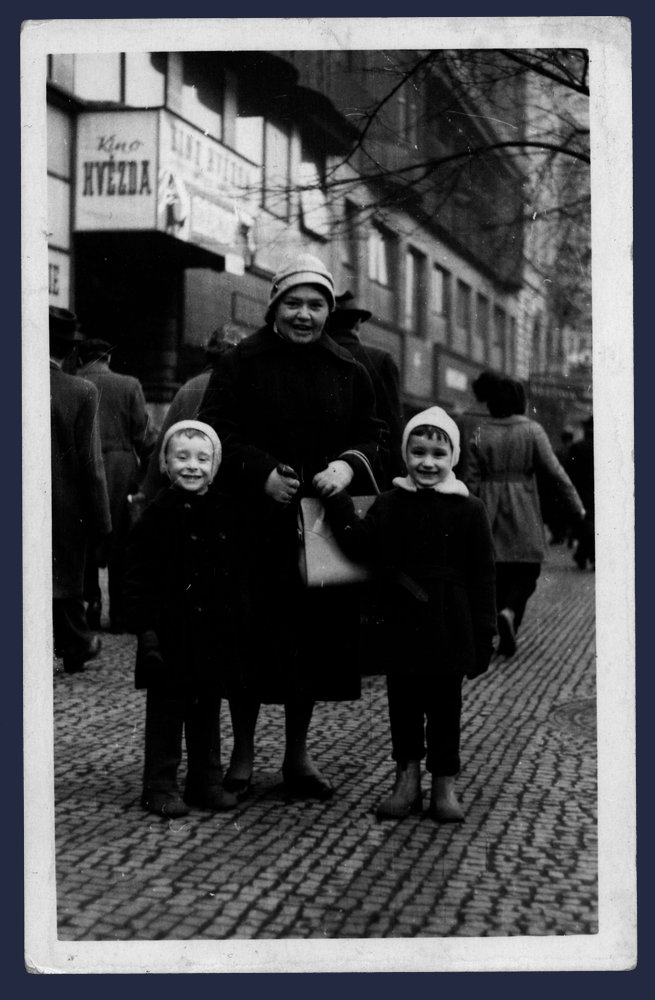

Jakob, nicknamed Jonny, Bamberger was born in Königsberg in East Prussia. His parents ran a traveling cinema throughout the countryside. In addition to the cinema, his father also dealt in horse trading. Sinti and Roma were banned from traveling in 1935, forcing the family to lease the cinema. Jakob Bamberger was working at the time for the Frankfurt am Main railway. In his free time, he was actively involved in boxing. He was German runner-up in the flyweight division and was initially appointed to the Olympic team for the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin. Before he could compete, however, he was expelled from the team as a result of the official policy of racial “cleansing” (“Säuberungen”).

Due to the increasing repression of the Sinti and Roma, Jakob Bamberger wanted to flee to Prague in 1941. However, he was arrested at the Czech border and sent to the Flossenbürg concentration camp in January 1942. He was forced to work in the “punishment squad” (Strafkompanie) in the camp’s stone quarry. Labelled as so-called “anti-socials” (“Asoziale”), Sinti and Roma like him occupied a low position in the prisoner hierarchy. He was subject to arbitrary beatings by the guards, which left his spine permanently damaged. The SS transferred him a year later to the Dachau concentration camp. There in the summer of 1944, he endured repeated abuse by being part of medical experiments in the infirmary. The camp doctors administered half a liter of seawater a day to him with the aim of researching how it could be made drinkable for fighter pilots shot down over water. He survived, but the dehydration permanently damaged Bamberger’s organs. After these excruciating weeks, he was sent to work producing Messerschmitt aircraft at a subcamp. Shortly before the end of the war he was deported to Buchenwald. By chance he was reunited there with his father. In April 1945 the Americans liberated Jakob Bamberger on a prisoner transport from Buchenwald to Flossenbürg.

After the war, Jakob Bamberger worked as a textile dealer and married in Munich in 1947. His wife, also a concentration camp survivor, died two years later, succumbing to health problems resulting from her imprisonment. He also learned that his mother and five siblings were murdered in Auschwitz. All his life Jakob Bamberger fought for the humane restitution for the physical damage inflicted on him during his imprisonment. He also campaigned for the official recognition of the persecution of the Sinti and Roma during National Socialism as well as the struggle for their civil rights after the war. He became the honorary chairman of the Central Council of German Sinti and Roma. In 1989 Jakob “Jonny” Bamberger died in Heidelberg.

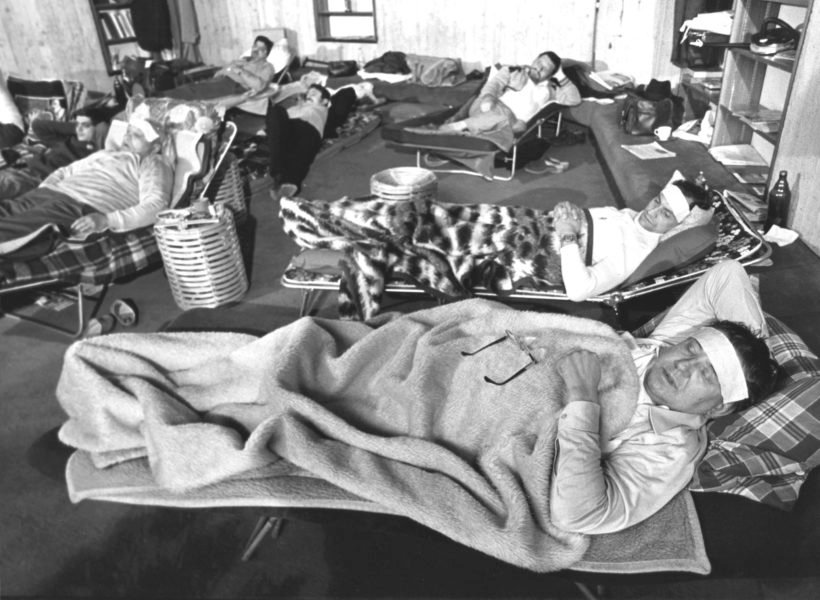

On Good Friday in 1980, a group of Sinti and Roma went on a hunger strike at the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial. They demanded the recognition of the Sinti and Roma as victims of National Socialism, as well as the state to be held accountable for the institutional discrimination of the Sinti and Roma after 1945. Many former concentration camp prisoners were among the protesters. One of them was Jakob Bamberger. During his three-year concentration camp imprisonment, he was subjected to forced labor, terror, and medical experimentation.

The Königsberg-born Jakob Bamberger from an early age was a fierce boxer, becoming the German runner-up in the flyweight division and making it to the Olympic team. However, before the games began, he was excluded from the team due to his origins.

Bamberger settled in rural Bavaria after the war and worked as a textile trader. Serious health problems made it impossible for him to return as a professional boxer. These were the result of medical experiments involving seawater that were performed in the Dachau concentration camp. His kidneys in particular were badly damaged. Yet, the German authorities rejected his claims for restitution on the grounds that the seawater experiments were more beneficial than harmful to kidney function.

For 20 years he fought for financial restitution. In 1969 he was finally granted the minimum pension. He used most of the pension to pay off the outstanding costs of the litigation. Almost nothing was left for himself.

Even decades after the end of the war, Sinti and Roma still endured institutional and social discrimination. Often it was the criminal investigators who were involved in the persecution of the minority before 1945 who wrote the evaluations for the compensation proceedings. When doing this, they used files from the Nazi era as references, insinuating that the victims of persecution were imprisoned in the concentration camps due to criminal acts. For decades this resulted in the denial of compensation for the injustices inflicted on the Sinti and Roma.

The hunger strike in 1980 raised widespread public attention for their demands. As a result, the Federal Chancellor Helmut Schmidt became the first German head of government to recognize the genocide of half a million European Sinti and Roma. To honor Jakob Bamberger’s commitment as an activist, Bamberger was appointed honorary chairman of the Central Council of German Sinti and Roma. Until his death in 1989, he remained politically active.

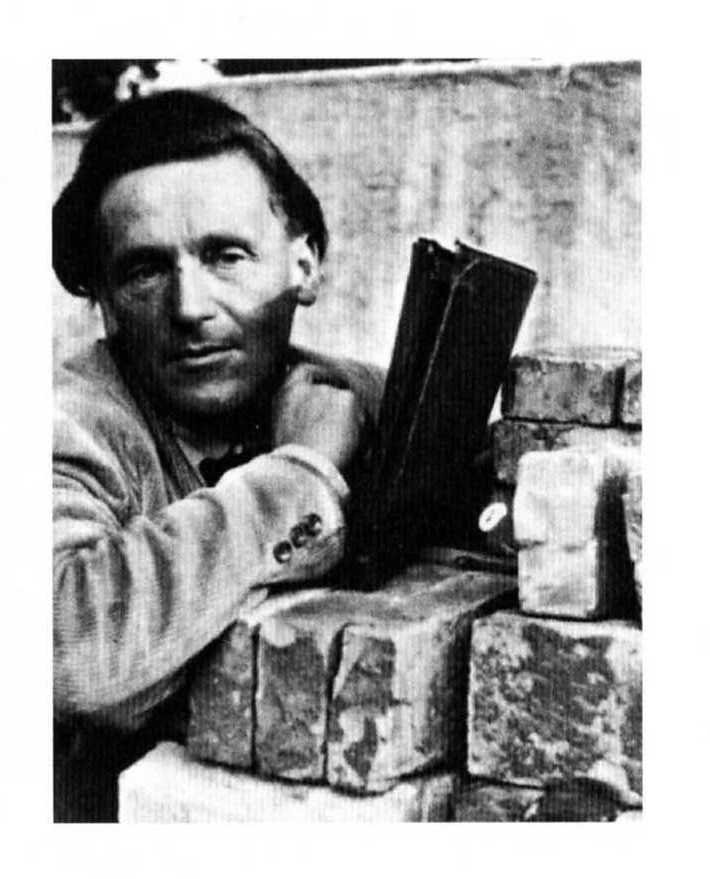

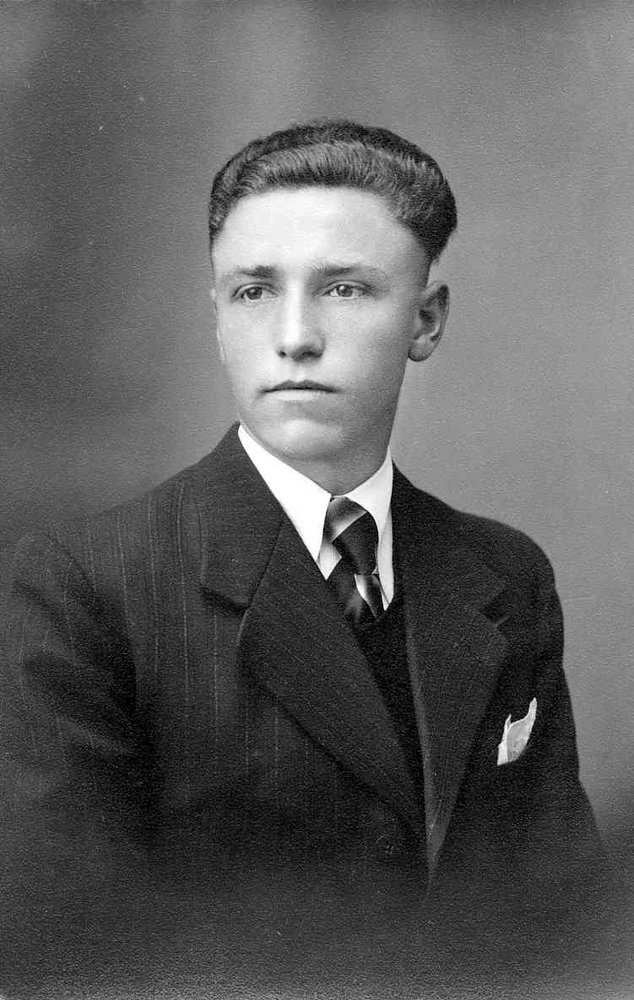

Marcel Durnez (November 28, 1926 – November 15, 2016)

Marcel Durnez grew up in the West Flanders province of Belgium. In 1943 his older brothers, Gilbert and Daniël, received the order to report to work for the Germans, which they refused to obey. Since the threat of being forcibly recruited was something Marcel also faced, he and his brothers fled to France. There they were betrayed and arrested by the Gestapo in March 1944.

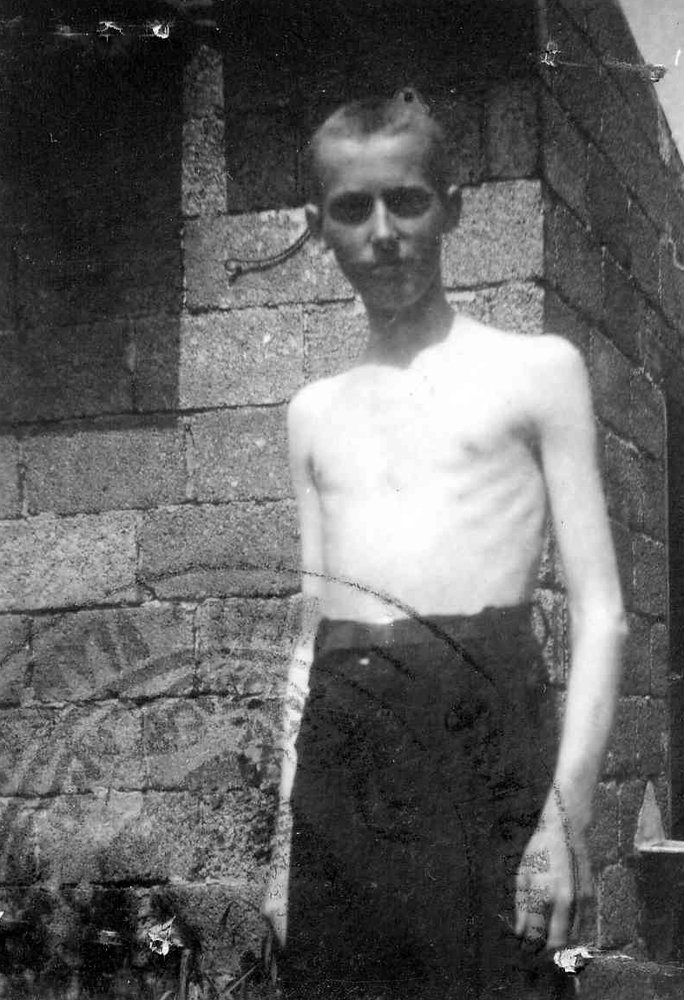

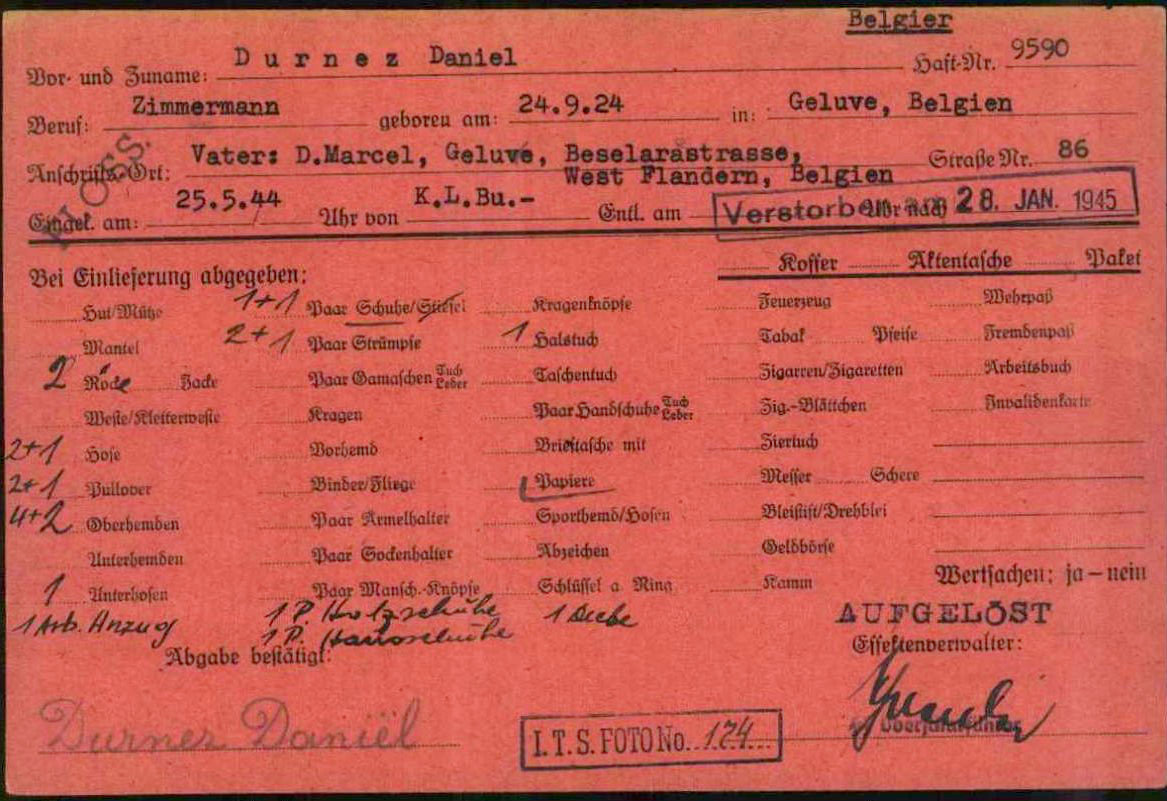

In May 1944 they were deported to the Flossenbürg concentration camp via the Auschwitz and Buchenwald concentration camps. A total of around 750 Belgians were imprisoned in the Flossenbürg concentration camp and its subcamps; just under 400 did not survive their imprisonment. When registering in Flossenbürg, the brothers of 17-year-old Marcel advised him to claim he was a carpenter. This saved him from working in the quarry. All three brothers were initially sent to work in the Messerschmitt factory, building aircraft. When work became scarce due to the lack of material, the SS transferred Marcel’s brothers to the quarry. There they performed hard physical labor. That was their eventual death sentence. Daniël Durnez fell ill and was taken to the infirmary. Marcel visited him there every day, but on January 28, 1945, he found an empty bed. Marcel Durnez found Daniël’s body in a pile of corpses in the washroom of the infirmary. He was able to identify him by the prisoner number on his forearm.

The other brother, Gilbert Durnez, injured his foot while working in the quarry. When he could no longer properly march, a kapo badly beat him. On April 13, 1945, ten days before the liberation of the Flossenbürg concentration camp, Gilbert died from the injuries sustained by the beating. Marcel Durnez was liberated on a death march to Dachau.

After his return to Geluwe, Belgium, Marcel Durnez could not face telling his parents about the fate of his brothers. They were only informed of their deaths via an official letter in the mail a few days later. After the war, Marcel Durnez worked as a weaver and later as a bricklayer. He married and eventually had a son.

Even if Marcel Durnez found it extremely upsetting to recall his experiences of imprisonment, he nevertheless visited the memorial in Flossenbürg several times with his family. At a young age, Marcel’s son, Yves Durnez, became interested in the history of his family. Yves’ parents, however, refused to discuss this with him due to the mental stress it would put on the father. It was not until the 1990s that the two spoke in regular, short sessions over the memory of National Socialism and the concentration camps.

“I had to tell my parents that my brothers were dead. I didn’t tell them right away. The letter that informed my parents of the death of my brothers arrived seven or eight days later. You can imagine how my parents felt. I, the youngest, came home and the bigger, stronger men didn’t.”

The brothers Daniël, Gilbert, and Marcel Durnez refused to work for the German occupiers in 1943. They fled their Belgian home to France. There they were arrested by the Gestapo. The three brothers were deported to the Flossenbürg concentration camp via the Buchenwald and Auschwitz concentration camps at the end of May 1944. In January 1945 Daniël Durnez fell seriously ill and died shortly afterwards. Gilbert, who injured his foot in the quarry, was badly beaten by a Kapo. Only days before the camp was liberated, he succumbed to his injuries on April 14, 1945.

In the concentration camps, life and death were generally a factor of chance occurrences. Those who survived were often plagued by guilt for the rest of their lives, especially when they saw the death of friends or relatives. Like many others, Marcel Durnez was tormented by the question of why he survived instead of his brothers.

"It is very difficult for him. It is incredibly difficult for my father to put these emotions into words. […] In the evening he wants to escape again, wants to run away again […]. Then he is back at the concentration camp. My mother doesn´t want to sleep then. And neither does my father.”

Marcel Durnez traveled to Flossenbürg several times with his family. When he thought about his time in the camp or talked about his imprisonment, he was often plagued by nightmares afterwards. "Ah, yes. I may have them again tomorrow evening. But I don’t know. Then everything comes back. [Yves Durnez] And then are these the images you see? [Marcel Durnez] That is...how should I say it? It’s just like it is back then. We should let it rest. And don’t think about it and don’t ruminate on it. That’s the best prescription.“

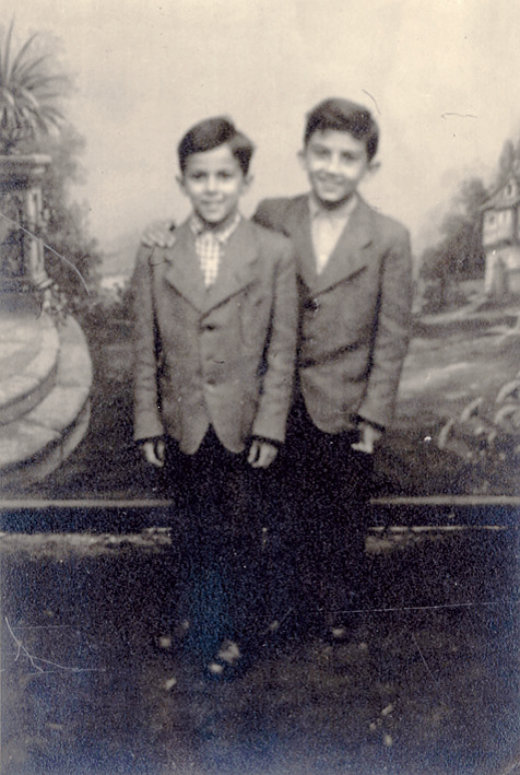

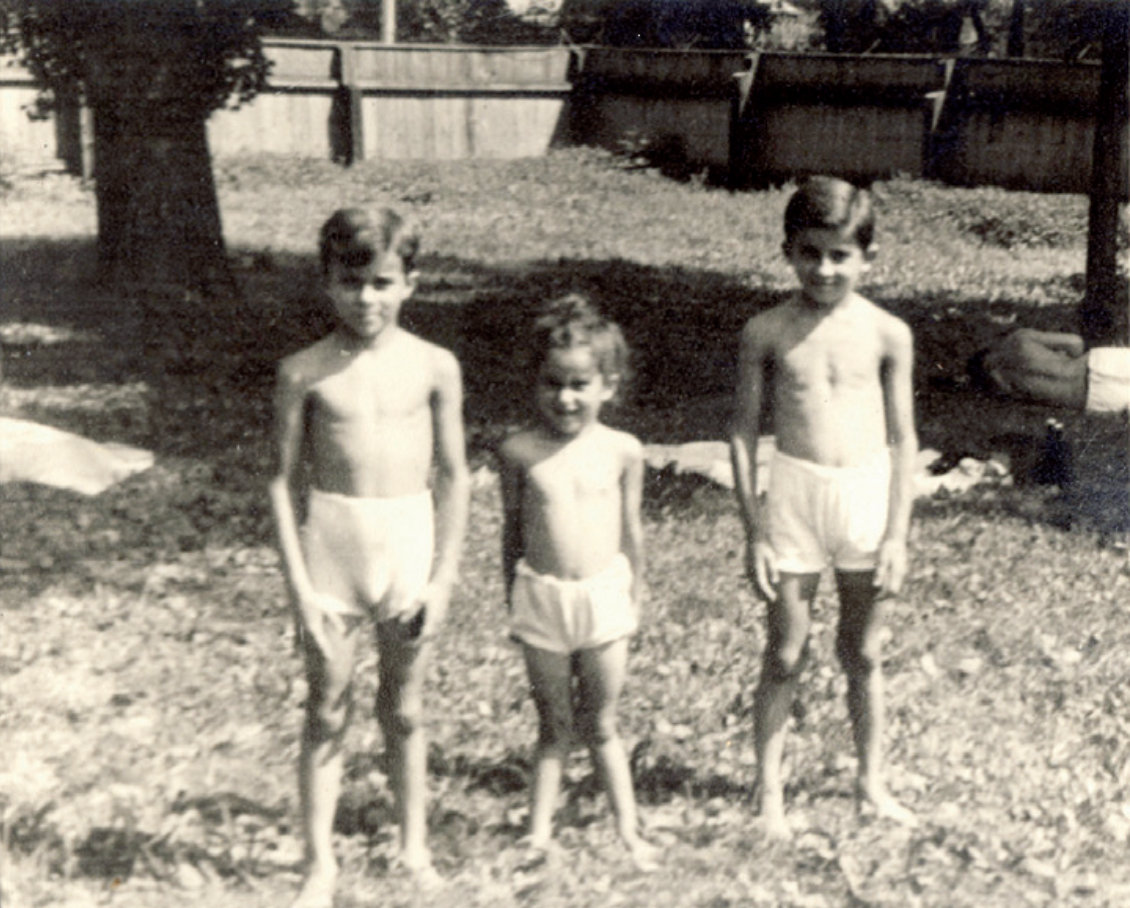

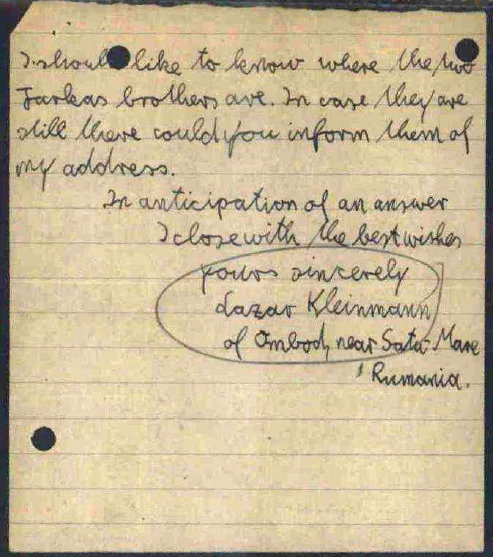

Leslie Kleinman (b. May 29, 1929)

Lázár Kleinman was born in Ambud, Romania, near the Hungarian border, as the second of eight children. His father, Mordka Kleinman, was a rabbi and teacher in his small village. Together with his wife Rosa Kleinman, he raised his children in a strictly religious manner.

When the region fell to Hungary, an ally of Germany, in 1940, the rights of the Jewish population were severely restricted. Shortly after the German troops marched in in April 1944, the situation worsened. Along with other men of the village, Mordka Kleinman was deported as a slave laborer. At this moment, Rosa Kleinman already suspected that the family would never see him again. Shortly afterwards, the rest of the family was deported to the ghetto in nearby Satu Mare and a few weeks later to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. Upon arrival, other inmates advised 15-year-old Lázár to claim he was already 17, a suggestion that saved his life. He was classified as “fit for work” and sent to do forced labor at the IG Farben in Auschwitz-Monowitz. This was, however, the last time that Lázár should see his mother and seven siblings.

As the Soviet armed forces were approaching in January 1945, the SS transported Lázár Kleinman to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, then three weeks later to the Flossenbürg concentration camp. Towards the end of the war, Lázár Kleinman was forced on a death march from Flossenbürg in the direction of Dachau. His two classmates, the brothers Zoltán and Erwin Farkas, aided the extremely weakened Lázár during the march, saving his life. On April 23, 1945, the prisoners were liberated by US soldiers.

Lázár Kleinman was the only one in the family who survived the war and its aftermath. His eldest sister Gitta died shortly after the end of the war, succumbing to the conditions of her concentration camp imprisonment, before Lázár and Gitta could see each other again.

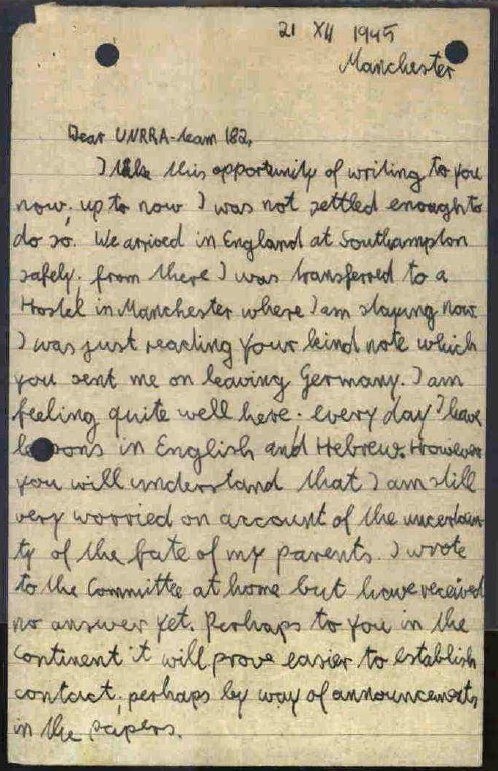

At first, Lázár Kleinman was brought to the International Displaced Persons Children’s Center Kloster Indersdorf. There he was reunited with the two Farkas brothers. In the fall of 1945 Lázár was given the opportunity to emigrate to Great Britain. Upon his arrival in England, he changed his first name from Lázár to Leslie. He established himself as a textile manufacturer and married his girlfriend Evelyn, a German non-Jew in 1956. They had two children. Seven years after the death of his first wife Evelyn, he married Miriam Stein in 2011.

When Lázár Kleinmann was liberated by US soldiers in April 1945, he and his sister Gitta were the only two of eight siblings who saw the end of the war. Yet before Lázár could see her again, Gitta died, succumbing to the conditions of her imprisonment in the concentration camps.

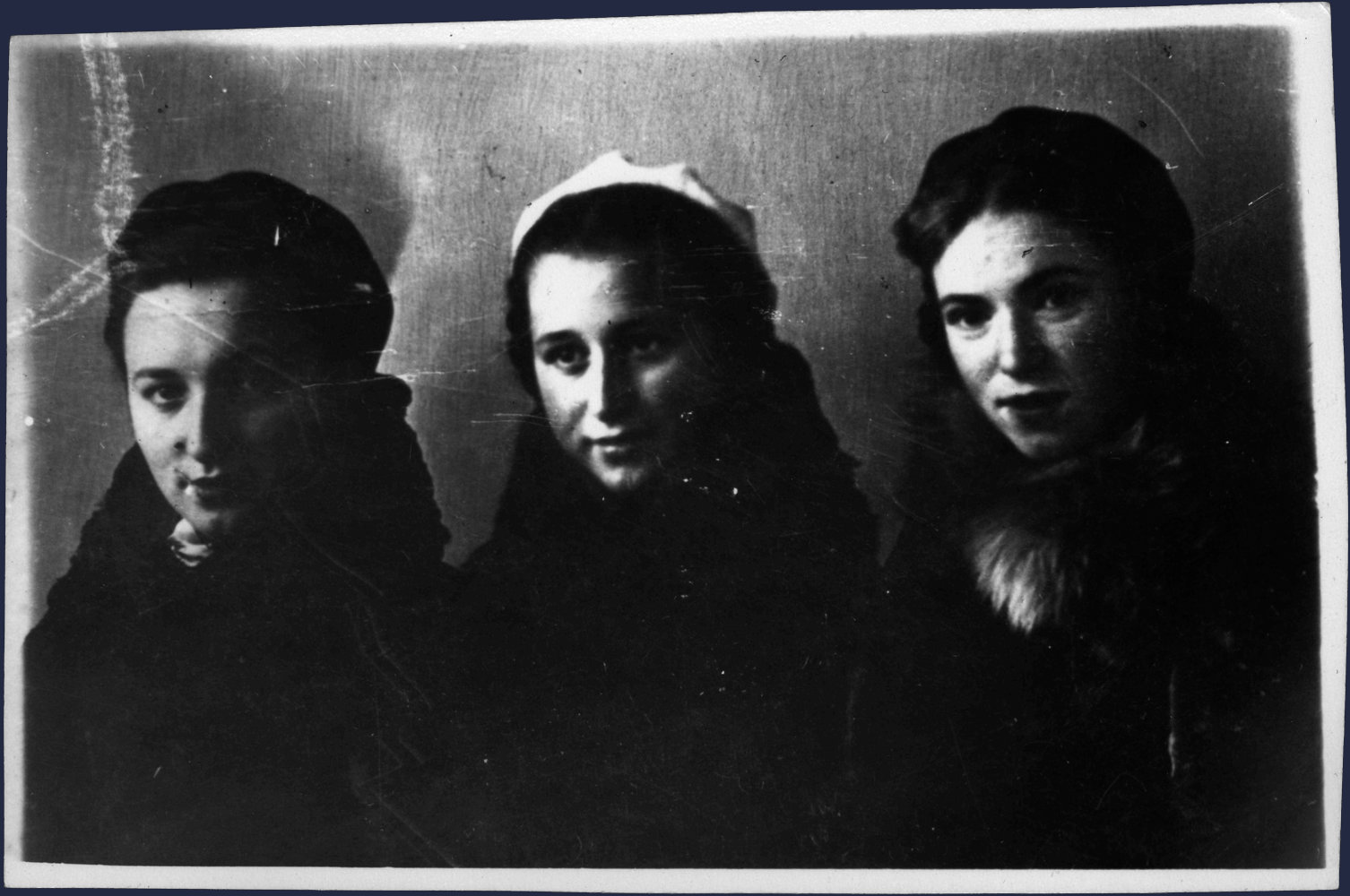

Like Lázár, many children and young people were left orphaned at the end of the war. 192 of them initially found refuge in the International Displaced Persons Children’s Center Kloster Indersdorf, near Munich. There the children and adolescents received regular meals and schooling, as well as medical care and psychological support.

The caretakers there encouraged the children to search for living relatives through advertisements. To support the search, the American photographer Charles Haacker was asked to take portraits of every boy and girl in the children’s home along with their name plaques. Many of these young people still recall this moment years later and the hope of being reunited with their loved ones. For others, however, it became a sad certainty that they were the only survivors of their families.

In Indersdorf, Lázár was reunited with two school friends, Erwin and Zoltan Farkas. With them, he not only bonded over shared memories of their home in the Carpathian Mountains, but also their experiences of concentration camp imprisonment and the death march. In the fall of 1945, Lázár left the Indersdorf monastery. He was given the opportunity to emigrate to Great Britain. When he arrived at his new home, he changed his name to Leslie. It was many years later before he could confirm with certainty that his parents and siblings were no longer alive.

In London, Leslie established himself as a textile manufacturer. In 1956 he married his first wife Evelyn, a German non-Jew. Despite his happy family life, memories of his deportation still haunt him.

“I was dreaming, you know, that the Nazis came again and took us again, in my dream, this is. And I said: „My god, I am seeing the people so clear.“ Walking with their little bags on their shoulders, with their families walking around them, and the guards.“ I still dreamed about it. And I saw so clear the way we left.“

After the death of his first wife Evelyn, Leslie married Miriam Stein in 2011. Leslie Kleinman has visited the Flossenbürg Concentration Camp Memorial numerous times. There he meets other “Indersdorf Boys.” With them Leslie shares the experiences of the war, the loss of family members, and the uprooting at a young age.